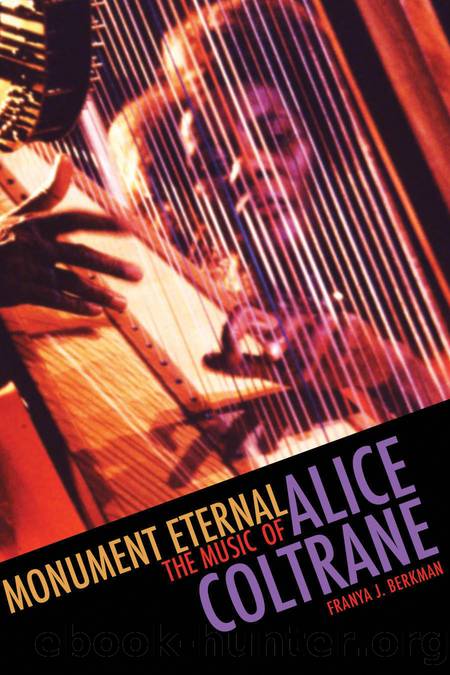

Monument Eternal by Franya J. Berkman

Author:Franya J. Berkman

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Wesleyan University Press

Published: 2010-03-15T00:00:00+00:00

Tapas, 1968â70

This first phase of Aliceâs spiritual transformation coincided with the music she made shortly after John Coltraneâs passing. From the time of her husbandâs death, she began to have extraordinary religious experiences. According to her description in her spiritual autobiography, Monument Eternal, the years 1968 to 1970 marked a period of spiritual purification for her, the first step on the path to spiritual enlightenment.1 During this period, she experienced insomnia and an inability to eat or communicate for lengthy periods. She even injured herself in several of her âexaminationsâ and was taken to the hospital on more than one occasion. Employing the term tapas, a yogic concept for spiritual austerity, she described her experience thus:

My tapas in this lifetime initially began with increased waking hours and extended meditations. Long fasts were maintained and sleepless vigils endured. Extensive mental and physical austerities caused my body weight to fall from 128 to 105 within a few weeks; later it was reduced to 95 pounds. My physical tapas consisted of a series of examinations on my reactions and aversions, specifically to heat and cold, light and darkness, life and death, joy and sorrowâi.e., on the dualities of life-polarization. (A. Coltrane 1977, 17)

From a psychiatric perspective, it might appear that Alice was experiencing extreme depression or psychosis. Having recently lost both her husband and a half-brother to whom she had been close, and burdened with the responsibility of raising four small children, she would have had ample cause. However, she described this time as a necessary period of purification: âThe mental and physical territories had to undergo purificatory spiritualization to bring about the expansion and heightening of my consciousness-awareness level . . . The Holy Spirit does not enjoy residing in an unclean heartâ (ibid. 13, 24). While this period of extreme âspiritual sufferingâ took place during the years shortly following her husbandâs death, she described her tapas as an ongoing process that has ânever ceasedâ (8).

The albums she recorded during this period, A Monastic Trio, Huntington Ashram Monastery, and Ptah the El Daoud, were extremely introspective and solemn. A Monastic Trio (1968)âher first solo album for Impulse!âwas an intimate expression of personal loss and a tangible reminder of John Coltraneâs musical and spiritual legacy. The liner notes also mark the beginning of her written communications with her audience, which would become increasingly extensive, mystical, and autobiographical.

The formal and improvisational techniques we hear on A Monastic Trio dominate her next two albums on Impulse! Recorded in the Coltrane Studio in Dix Hill, New York, with Rudy Gelder and Roy Musnug (her late husbandâs producer and technician) presiding, the albumâs session consisted of Alice Coltrane, on piano and harp, and John Coltraneâs former sidemen: Jimmy Garrison on bass, Pharoah Sanders on saxophone and flute, and Ben Riley and Rashied Ali alternating on drums. Of the nine tracks on A Monastic Trio, eight are in minor modes, and five make use of rubato chord progressions that swell and ebb with a definitive weightiness. Alice also composed several elegies for her husband, among them âOhnedaruthâ and âI Want to See You.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31956)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31941)

Fanny Burney by Claire Harman(26602)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19046)

Plagued by Fire by Paul Hendrickson(17412)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(16026)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15352)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(14121)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14074)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13336)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12392)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8999)

Adultolescence by Gabbie Hanna(8927)

Note to Self by Connor Franta(7671)

Diary of a Player by Brad Paisley(7577)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7346)

What Does This Button Do? by Bruce Dickinson(6207)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(5447)

Born a Crime by Trevor Noah(5382)